Feline Heartworm Disease

Feline Heartworm Disease

No Cat is Safe . . .

From Heartworms!

Most people know that heartworms are prevalent in the dog population and are used to giving their dog a monthly heartworm preventative, but did you know that your cat is at risk too?

Meet Pip. Pip is a 1 year old, neutered male long haired domestic cat who lives primarily indoors, only going outside on a leash for brief adventures. Pip began having episodes of open mouth breathing or “panting” after minimal exercise five months ago. The episodes resolved until recently. Worried that he may have a heart condition common to long-haired cats called Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, Pip had x-rays taken of his chest and then an ultrasound of his heart or echocardiogram.

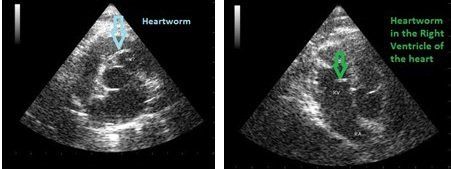

Pip’s x-rays were unremarkable. His ultrasound, on the other hand, was quite informative. Pip was diagnosed with a heartworm infection after heartworms were visualized in the heart on ultrasound. Blood tests including a heartworm antigen test and heartworm antibody test both showed negative results. Pip’s story has many important points which we will explore shortly. 1) Pip is an “indoor” cat, long-haired, and young. 2) Pip showed signs briefly, seemed to get better, and became symptomatic again a few months later. 3) Pip’s x-rays were normal and his heartworm antibody and antigen tests were negative.

Heartworms are internal parasites which are spread from an infected animal to an uninfected one by mosquitoes. It only takes one mosquito getting into the house and biting the cat to cause an infection. Because cats have different immune systems than dogs, they respond differently to heartworms. Many of the juvenile heartworms are actually destroyed by the cat’s immune system long before they reach the heart, but if even 1 or 2 heartworms survive to adulthood in a cat they can cause disease as significant as 60 heartworms in a dog! Even juvenile heartworms can cause a cat to be sick before the cat’s immune system kills them. Cats initially show signs of heartworm disease when larval forms of the heartworm migrate from the blood stream into the lungs roughly 3 to 4 months after initial infection, causing a syndrome known has HARD (Heartworm Associated Respiratory Disease) which includes mild intermittent cough, asthma-like symptoms, increased respiratory rate or effort, reduced appetite, vomiting and diarrhea, weight loss, blindness, collapse, convulsions, lethargy, and even sudden death.

The life span of an adult heartworm in the cat is roughly 2 to 3 years. When the heartworm dies, the cat is again likely to show signs of infection as the parasite degenerates and causes increased inflammation in the lungs and even clots in the bloodstream called thromboembolism. Cats may also have an overwhelming allergic reaction. Some cats never show any signs of heartworm disease at all but lung and heart damage is still found after they pass away.

Because cats have such a low worm-burden, diagnosis of heartworm disease in cats is often very difficult. Blood tests which look for antibodies to the heartworms may only be positive in cats for a brief period of time after their initial infection, only indicate exposure to the heartworm larva but not active infection, and may be false positive or false negative just like any other test. Blood tests which look for heartworm antigen will only be positive if an adult FEMALE heartworm is present because they test for proteins produced by female heartworms – 50% of cats will have a male-only infection which would not be detected by this test – and may also be falsely positive or negative. While there are many signs on x-rays which may be present due to heartworm disease, no signs are specific to heartworm disease and some cats may not have any radiographic evidence of infection! Cardiac ultrasound is dependent on the experience of the ultrasonographer, compliance of the patient, and location of the heartworm. A combination of all diagnostic tests may be necessary to positively identify heartworms in a cat. If a cat were to be antigen positive on two antigen tests (retesting is always recommended to rule out a false positive), heartworms were identified on ultrasound, or significant radiographic change was noted in conjunction with either test, an active heartworm infection would be confirmed in a cat. A positive antibody test would only indicate previous exposure and a heartworm antigen test and x-ray or ultrasound should be run to confirm active infection. It is possible, if unlikely, for a cat to have no evidence of heartworms on all of these tests and still be infected. Ultimately, there are several ways to prove heartworm infection but no way to conclusively rule out heartworm infection in a live cat.

Most people would think Pip didn’t need to be on heartworm prevention because he is indoors only – but mosquitos frequently get into any household and can find their way to a warm-bodied animal with relative ease. Most people would also think that Pip would be protected by his long hair – but haven’t you gotten a mosquito bite through clothing or on your scalp? Pip’s youth would also lead most people to think it would be impossible for him to have heartworms, but it only takes 4-5 months for a heartworm to reach adulthood in a cat and the summer months are the most common time of transmission, coinciding perfectly with Pip’s history.

Pip’s intermittent symptoms also follow the typical course of heartworm disease, showing up at first when the larvae migrate into the lungs, then only intermittently until the heartworm dies.

Pip’s case also presents how difficult it is to diagnose heartworm disease in cats. Pip showed no radiographic evidence of heartworm disease, his blood tests were negative, and it was only on ultrasound that heartworm infection was identified! Pip has only 1 or 2 heartworms, a very common occurrence in cats, and both heartworms are likely to be male, resulting in a negative antigen test. His heartworm antibody test is either false negative or his body is not actively producing a high number of antibodies against the heartworms, anther common occurrence in cats. X-rays are relatively insensitive in identifying heartworm disease in cats but can be very good indicators of the extent of infection and damage to the body if signs are present on x-rays.

So what happens to Pip now that we have diagnosed a heartworm infection? Because cats can’t receive the same heartworm treatment as dogs do, it is very difficult to treat cats for heartworm disease. Immiticide, the treatment we use in dogs, is not at all tolerated in cats and can’t be used. The only other option to definitely treat heartworms in cats is to surgically remove them, a procedure which is very risky and expensive. Often, we treat cats with heartworm disease symptomatically and supportively while the heartworm ages and dies. If a cat is symptomatic for infection (is showing signs like respiratory distress, vomiting, lethargy, or any other sign), those symptoms are treated. Most cats with heartworm disease are also started on steroids to decrease the inflammation associated with the infection and hopefully decrease the likelihood of an allergic reaction should the heartworm die and begin to break apart. A monthly heartworm preventative is given every month to weaken the adult worms and to prevent infection with more heartworms. A third medication is used to help shorten the lifespan of the heartworm by killing a bacteria called Wolbachia which helps support the heartworm; this medication is an antibiotic called doxycycline. Treatment is always determined on a case-by-case basis and depends on many factors which our veterinarians take into account to decide which treatments best fit each cat and their owners.

What is the best way to save your cat from heartworms? Use a monthly heartworm preventative every month, year-round. Many heartworm preventatives also prevent intestinal parasites which may be contagious to people, protecting you and your pet at the same time. Certain heartworm preventatives also prevent fleas and earmites!

While heartworm disease is slightly less common in cats and the worm-burden is often lower, heartworm disease in cats is much more difficult to diagnose, treat, and survive. Please think of Pip the next time you hear someone say their indoor cat doesn’t need to be on heartworm prevention.

Pip is an actual patient and his owner has been kind enough to allow us to share his story in hopes that he can save other cats from a similarly uncertain fate. Pip is alive and well as he undergoes treatment for heartworms by supportive care.

If you have any questions, please feel free to call us anytime. You can also visit the American Heartworm Society’s website for more information

Find Us

University Animal Hospital of Greensboro PLLC

1607-B West Friendly Avenue

Greensboro, North Carolina 27403

PHONE: 336-279-1003

universityanimhosp@bellsouth.net

Online Pharmacy: https://universityah.myvetstoreonline.pharmacy

Contact Us

Thank you for contacting us.

We will get back to you as soon as possible

We will get back to you as soon as possible

Oops, there was an error sending your message.

Please try again later

Please try again later